Proton therapy offers more precision, fewer side effects for head and neck cancer patients

April 09, 2015

Medically Reviewed | Last reviewed by an MD Anderson Cancer Center medical professional on April 09, 2015

The good news is death rates continue to decline for the most common types of cancer, including lung, colon, breast and prostate.

The bad news is a far less common head and neck cancer is rising sharply. Since the late 1980s, cases of oropharyngeal cancers that attack the back of the throat, the base of the tongue and the tonsils have jumped 225%. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, almost three-fourths of the cases are linked to HPV, the human papillomavirus.

Even when diagnosed in late stage, most oropharyngeal cancers can be cured. But the radiation therapy traditionally used to treat head and neck cancers can cause debilitating side effects, including mouth and gum ulcers, difficulty swallowing, loss of appetite and the need for feeding tubes and hospitalization.

“Radiation destroys the cancerous cells, but it also destroys healthy cells, which can cause painful and difficult side effects,” explains Steven Frank, M.D., associate professor of Radiation Oncology.

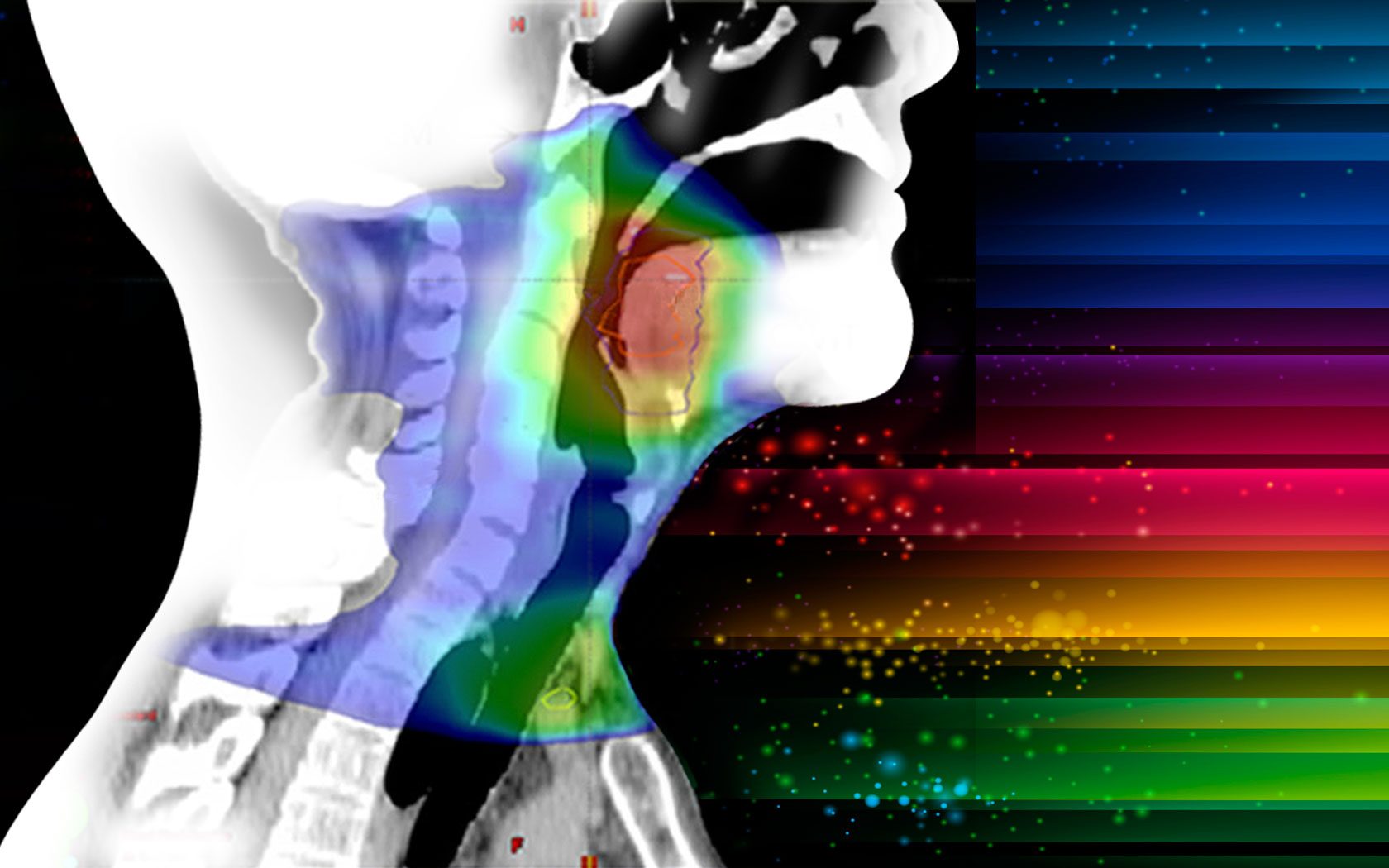

In 2010, MD Anderson’s Proton Therapy Center, where Frank serves as medical director, became the first site in North America to treat patients with intensity modulated proton therapy (IMPT). The technique uses an intricate network of magnets to aim a narrow proton beam at a tumor and “paint” the radiation dose onto it layer by layer. Healthy tissue surrounding the tumor is spared, and side effects are reduced.

A small but promising study conducted by MD Anderson last year showed that oropharyngeal cancer patients treated with IMPT needed feeding tubes only half as often as patients treated with standard radiation therapy. The study also showed that toxicity levels were dramatically lower in IMPT patients compared to patients treated with standard therapy.

A second MD Anderson study treated 15 head and neck cancer patients with an advanced form of IMPT, known as multi-field optimization intensity modulated proton therapy (MFO-IMPT). The treatment maps the location, size and dimensions of hard-to-reach, complicated tumors, then sends a potent dose of protons to attack the tumors in the “nooks and crannies” of the head and neck or skull base where they live, says Frank, the lead investigator of both studies.

Two years and four months after the study concluded, 93% of participants remained cancer free. During treatment, all reported that side effects were greatly reduced, prompting some radiologists to label IMPT the “holy grail” for head and neck cancers.

With these promising findings, MD Anderson, in collaboration with Massachusetts General Hospital’s Francis H. Burr Proton Therapy Center, has been awarded a $20 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to further study the role of IMPT in the treatment of head and neck cancers. The first randomized study has been opened to patients, with additional trials expected later this year.